I recently read The Blazing World by Margaret Cavendish, a science fiction novel published in 1666, re-issued in a Penguin edition edited by Kate Lilley. Lilley’s introduction describes Cavendish as a striking figure in her time, a woman who sought publication and fame in her own name, who “represented herself as figuratively hermaphrodite” in combining masculine and feminine elements of dress, who was first thought to not be the true author of her works and later expressed frustration at not receiving the acclaim for her work that she wanted. Harriet Burden describes her as “a beardless astonishment, a confusion of roles”: a fitting inspiration for her final work, titled The Blazing World, which gives its title to the entire novel about her.

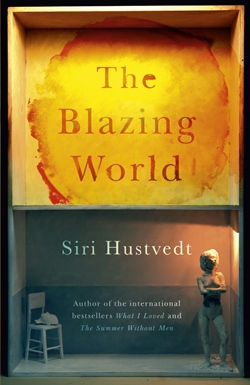

The Blazing World by Siri Hustvedt is about art, women and men, and what happens when those supposedly separate genders are not so separate.

It is about the artist Harriet Burden, known as Harry to her friends, who received little acclaim for her early exhibitions. Later in her life, she enacts a project: three exhibitions of her work with a different man as the “Mask” for each, publicly presented as the true artists, to prove that sexist bias favours men. The exhibits are acclaimed. The “unmasking” goes poorly. Only after her death does attention seem to be turning to Harry, who is the subject of the documents gathered by scholar I.V. Hess in The Blazing World.

The first thing to note is I.V. Hess’ name: unmarked by gender. Hess’ gender remains unrevealed throughout the book, although there is one interesting incident where Hess becomes impassioned in an interview with a person who worked with Rune, the third Mask, who took credit for the work exhibited in his name. Hess admits to having “been carried away” in the interview. I.V. Hess is, like Mars in Kelley Eskridge’s “And Salome Danced,” interesting for not being gendered. Where does Hess fit in the gender relations of the book? An angry, triumphant woman; an understanding man; a fascinated person in the space cautiously opened up between the two?

That space is opened—or crossed—at several points in the book.

In a description of the first exhibit:

“Story 2. Another room with sofa, two chairs, coffee table, bookshelves. On the table is a torn piece of paper with Don’t printed on it. Beside it: small wooden coffin with more words: she/he/it. Tiny painting hangs on wall. Portrait of figure looking much like girl in story I but boyish—arms raised, mouth open.”

A figure in her second exhibit, which Harry says “had to come from ‘another plane of existence’,” is described as “skinny, eerily transparent… hermaphroditic (small breast buds and not-yet-grown penis), frizzy red human hair.” It is notable that Harry’s hair is remarked on for its wildness. Then: “The really large (by now) metamorphs have finally noticed that the personage is out and have turned their heads to look at it.”

Phineas Q. Eldridge, the Mask for her second exhibit, a mixed race man who performs on stage prior to meeting Harry as half-white/half-black and half-man/half-woman, says of Harry:

“She didn’t truck much with conventional ways of dividing up the world—black/white, male/female, gay/straight, abnormal/normal—none of these boundaries convinced her. These were impositions, defining categories that failed to recognize the muddle that is us, us human beings.”

And, several pages later, Phineas confirms the hermaphroditic figure’s metaphor:

“It’s Harry crawling out of that box—thin-skinned, part girl/part boy little Harriet-Harry. I knew that. It’s a self-portrait.”

It’s already apparent that the book’s troubling of the gender binary is defined by the binary, not by stepping (far) outside it: the hermaphroditic figure is male and female, not neither. This is echoed elsewhere. Harry raises the question of what if she had been born male, a gender more matched to her height and manner. Harry parodies her first Mask’s male posturing by re-enacting his gestures to a friend in a feminine manner: she “played” him as a girl. Harry and Rune play a dangerous game of masking, before the third exhibit, where Harry wears a male mask and Rune wears a female mask.

An essay by Richard Brickman (a pseudonym for Harry) says:

“Each artist mask became for Burden a ‘poetized personality’, a visual elaboration of a ‘hermaphroditic self,’ which cannot be said to belong to either her or to the mask, but to ‘a mingled reality created between them.’”

This mingled reality appears to be one in which female and male are mixed. Harry quotes Cocteau at Rune: “Picasso is a man and a woman deeply entwined. He is a living ménage.” Earlier, when Harry and Rune discuss Philip K. Dick and Boolean two-value logic, Harry writes: “I asked him if Dick had advocated a three-value logic…. Three values includes true, false, and the unknown or ambiguous.” Elsewhere, androgynous is defined by Harry as “both boys and girls.”

Harry’s son, Ethan, writes:

“Why the number two? E thinks of doubles, twins, reflections and binaries of all kinds. He hates binary thinking, the world in pairs.”

E is short for Ethan, but it’s interesting (perhaps intentional, perhaps not) that ‘E’ is also the Spivak pronoun.

The coffin in the first exhibit is marked “it” (not a pronoun many non-binary people want to use, but by definition neither female nor male) as well as “she” and “he”. I.V. Hess is ungendered. There is a small space here, I think, between female and male—but it is small. There is certainly a troubled, tense fluidity between the binary, a desire to be both genders—but not neither—and it is important. The hermaphroditic figure in the first exhibit must be looked at by the metamorph figures.

I said of Siri Hustvedt’s The Blazing World in my last post that it “crosses the binary so much that it starts to cross it out.” Does it? Or is it too rooted in the binary: opening and (nearly) closing with direction associations between genitals and gender, focusing on the conflicting experiences of women and men in the arts. It’s a troubling book. It troubles. It speaks, perhaps, to the reality of life in a binary-centric culture, the daily troubling of the binary we do without being able to go to the worlds of science fiction where we can go beyond it. It’s a book about male and female: their opposition, their crossing-points. The line between them is not at all sure. Does crossing that line cross it out or emphasise it? Both? Certainly both is this book’s concern, not neither (to paraphrase Amal El-Mohtar in one of our conversations about the book).

Harry writes of Margaret Cavendish:

“Cross-dressers run rampant in Cavendish. How else can a lady gallop into the world? How else can she be heard?… Her characters wield their contradictory words like banners. She cannot decide. Polyphony is the only route to understanding. Hermaphroditic polyphony.”

Cavendish was permitted to visit the Royal Society in 1666. The first women were admitted to the Society in 1945. There are almost three centuries between those dates. Cavendish is talked of now, when people remember that men don’t have an exclusive grip on the early works of science fiction. It takes time to change. I think of this when I feel frustrated at how deeply rooted Hustvedt’s The Blazing World is in the binary, yet sympathetic with its characters’ situations. The book is aware of science fiction: Harry tells her daughter about James Tiptree Jr. and Raccoona Sheldon (and Alice Bradley Sheldon beneath those masks), although the possible complexities of Sheldon’s gender are elided by the metaphor of masks. From a science fiction perspective, I find Hustvedt’s The Blazing World to be a reminder of our contemporary situation—our society’s still-early strainings against the binary—which contextualises our science fiction, which is not as far from Sheldon’s time as we’d like. In the contemporary, we’re limited. In science fiction, why be? The centuries—millennia—will have passed.

Alex Dally MacFarlane is a writer, editor and historian. Her science fiction has appeared (or is forthcoming) in Clarkesworld, Interfictions Online, Gigantic Worlds, Solaris Rising 3 and The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy: 2014. She is the editor of Aliens: Recent Encounters (2013) and The Mammoth Book of SF Stories by Women (forthcoming in late 2014).

Looking back on your columns on this subject, I haven’t seen mention of a couple of authors that came to my mind. (Not trying to be provocative, but all the authors cited so far seem to be female.)

Theodore Sturgeon — Venus Plus X a 1960 novel about a utopian hermaphrodite society.

And John Varley’s “Eight Worlds” series, in which changing gender is as easy and as common as getting a tattoo. Steel Beach (1993) the protagonist does this about a chapter in. A short story, “Options” (1979) is all about a woman who becomes male (for a while) and the effect on her family. Actually Varley’s stories are the most “post gender” I’ve seen, and he does it mostly organically in the story or background.

And Heinlein’s “All You Zombies” 1959 involves an (involuntary) sex change by the protagonist, though it’s really more of a time paradox puzzle story than anything else.